Since the beginning of 2024, major investment pledges to Central Asia and notable international public listings by Kazakh companies have cemented the region’s position as a new frontier for investment. Although the rewards for betting on the region may be significant, compliance, sanctions, and geopolitical risks persist. In this article, S-RM Senior Analyst Quinton Scribner and Senior Associate Penelope Jenkins discuss the opportunities and risks foreign investors need to weigh up when considering investment in Central Asia.

On 30 January 2024, the European Commission announced an EUR 10 billion public-private investment pledge to support the Transcaspian Transport Corridor, also known as the Middle Corridor, a trade route connecting Europe and China via Central Asia, the Caspian Sea, and the South Caucasus. This announcement stands out against other big promises to invest in the Middle Corridor – such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative – as much of the financial commitment comes from the private sector. If successful, an improved Middle Corridor could help overcome key infrastructure bottlenecks and substantially reduce shipping times, all while avoiding jurisdictions heavily targeted by sanctions, such as Russia and Iran.

Institutional and retail investors have also been drawn to recent international public listings by two of Kazakhstan’s leading companies. In January 2024, AO Kaspi.kz – the company behind a ‘super app’ that encompasses banking, consumer finance, and e-commerce – raised USD 1 billion in its Nasdaq debut for a valuation of USD 17.5 billion. It was the first Central Asian company to list in the US, where it is now re-orienting its listing from the London Stock Exchange. In February 2024, Kazakhstan’s national airline AO Air Astana listed on the London Stock Exchange, raising USD 120 million for a valuation of USD 847 million. International investors have also been drawn to Uzbekistan’s far-reaching privatisation initiatives. In June 2023, Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Economy sold a majority stake in AKIB Ipoteka Bank, the country’s fifth-largest financial institution, to Hungary’s OTP Bank plc.

These developments underscore growing interest from the international private sector in Central Asia. Not only does the region have increased strategic significance since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine two years ago, but its business environment continues to attract interest from around the world. While businesses may be rewarded for betting on the region, investors must go into these environments with their eyes open to the compliance, sanctions, and geopolitical risks associated with the region.

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan’s emergence as leading regional destinations for foreign investment

Foreign investment in Central Asia has long gravitated around Kazakhstan, the largest economy in the region. Exports of natural resources have been a mainstay of Kazakhstan’s economy – particularly oil, gas, and coal. In recent years, the country has positioned itself as the region’s leading voice on the green energy transition. Kazakhstan is the world’s largest producer of uranium with 40 percent of global production, and together with Uzbekistan – another significant uranium exporter – also sits atop substantial reserves of the critical minerals required for renewable energy generation and battery production. Kazakhstan has significant potential to become a leading producer of green hydrogen, an emissions-free fuel source produced using renewable energy resources that could one day fuel heavy industry and transportation. These efforts are supported by an ambitious reform agenda to strengthen state institutions and support market reforms.

Meanwhile, Uzbekistan has begun to position itself as a competitive destination for foreign investment. Since the death of president Islam Karimov in 2016 and the accession to the presidency of Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan has embarked on an ambitious reform programme centred around improved human rights and economic liberalisation. In 2022, international civil society groups credited the Uzbek government for successfully abolishing the longstanding practice of forced labour in the production of cotton and called for an end to a global boycott of Uzbek cotton. The government has also pledged to invest heavily in agriculture to increase output and raise incomes across the agricultural sector, which accounts for a quarter of GDP and employment. Uzbekistan is additionally seeking to leverage its geography to become a strategic destination for manufacturing in Central Asia, notably the production of electric vehicles. But perhaps its most significant advantage is its human capital: the country’s large, digitally-savvy population of 35 million – 60 percent of whom are under the age of 30 – offers significant opportunities for IT outsourcing to Uzbekistan.

Regional risks persist

Corruption, sanctions, and geopolitical risks nonetheless persist in Central Asia and potential investors need to evaluate these alongside their commercial considerations. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, the economies of Central Asia have been defined by a high degree of state participation in the economy and close ties between politics and business. Control of key industries is often concentrated in small groups of individuals who are politically connected, protected by a judicial branch that is heavily influenced by the political elite, and frequently favoured in public procurement. This exposes companies operating in the region to significant corruption risks.

While Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have sought to paint the picture of a more welcoming destination for foreign investment, neighbouring Kyrgyzstan’s reputation as an island of democracy and supporter of investor rights has weakened. In 2021, the Kyrgyz government nationalised the Kumtor gold mine, which had been majority owned and operated by the Canadian mining company Centerra Gold Inc. This prompted a series of legal disputes until a settlement was reached in 2022. The Kyrgyz government has also applied pressure to the country’s robust civil society: a proposed ‘foreign representatives’ law is expected to tighten the state’s grip over civil society, and it follows the closure of some of the country’s most respected anti-corruption and investigative media outlets. While still a far cry from the autocratic regimes in Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan’s democratic backsliding has lessened the international business community’s confidence in the country.

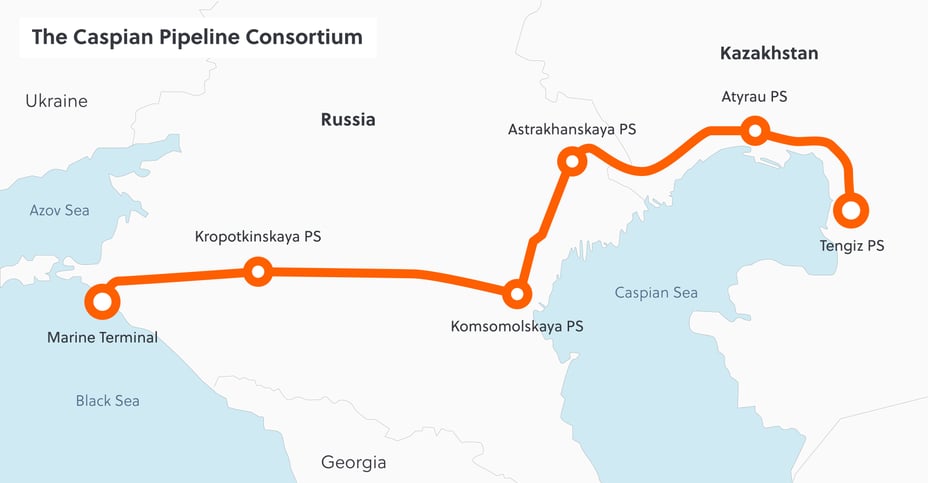

Sanctions against Russia have also muddied the business environment in Central Asia. The region’s economies are highly dependent on Russia through trade, energy, and migration. Kazakhstan is particularly exposed to the Russian economy, given that 90 percent of its exports run via Russia, including 80 percent of oil exports through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium to the Black Sea. While the governments of the region have expressed a commitment to uphold the international sanctions regimes against Russia, enforcement has been extremely difficult. This is further complicated by the growth of so-called ‘parallel imports’ across the region, whereby consumer and industrial goods – some of which are subject to Western sanctions – are exported to Russia via third countries, many of which are in Central Asia. In a bid to curtail this sanctions evasion, western regulators have sanctioned entities and individuals across the region for exporting goods to Russia in breach of sanctions regimes. Most recently, in February 2024, both the US and EU targeted persons and entities across a number of countries, including Kazakhstan.

Finally, investors will need to be mindful of the changing geopolitical dynamics in the region. Until February 2022, Russia considered itself the region’s main security guarantor – best exhibited by its prompt intervention in support of Kazakh president Kassym-Zhomart Tokayev’s government after major unrest and an attempted coup in January 2022. But other countries are starting to expand their influence in the region. While China has long pursued deeper economic linkages in the region, since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, it has projected itself as a reluctant security guarantor. Turkey is also pursuing deeper diplomatic ties, and increasingly security engagement in the region. Against this backdrop, the countries of Central Asia have sought to revamp a ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy in order to carefully balance their interests against those of Russia, China, and the West.

Conclusion

The European Commission’s investment pledge to support the Middle Corridor and Kaspi.kz and Air Astana’s international public listings have bolstered Central Asia’s image as a destination for foreign investment. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have emerged as the region’s leaders in this regard thanks to their rich mineral deposits, green energy potential, and far-reaching reforms. While betting on the region may reap significant rewards, investors must enter transactions with their eyes open to the compliance, sanctions, and geopolitical risks that persist in Central Asia.