Traditionally cyber security has been divided between red teams who simulate attacks and blue teams who focus on how to respond to them. In this article, Vlada Kulish and Tim Geschwindt challenge this false dichotomy, arguing for a multidisciplinary approach to incident response.

This article is the third in a special series on Cyber Incident Response culminating in an S-RM IR Bulletin in January 2024. Missed last week's instalment? Read Derailing Akira: stopping a cyber-attack in its tracks now.

The status quo

In an infamous scene in the US hit film The Matrix, the protagonist – Neo – is presented with a choice by one of the leaders in the story, Morpheus. Morpheus stretches out his hands: in the palm of his left hand is a red pill, and in the palm of his right, a blue pill. The choice presented to Neo is a dichotomous one: there are no blurred lines, just a binary choice between one path or another.

While the choice between red or blue in cyber security has less impactful ramifications than the one Neo faced in the Matrix, the cyber security industry has fallen into the paradigm where someone must be either the defender (blue), or the attacker (red). The decision is often a commercial one. Those who choose blue join a company’s incident response practice with a clear service to offer clients; whereas those who choose red join the same company’s penetration testing or ethical hacking team. The services offered are clear and clients are familiar with the difference.

At S-RM, while we have both an Incident Response team and an Offensive Security team representing blue and red respectively, the lines between the two deliberately become increasingly blurred during our responses to major incidents. Here’s why.

The challenge

Incident responders face a significant challenge in almost all major response cases: while we might eventually receive enough evidence to analyse and reach an assessment of what the threat actor did, and how they did it, we frequently end up in a situation where the evidence will only be available days after the incident, or there is no evidence available at all.

In cases like this, the onus is on the incident response team to provide answers to the client regarding how the threat actor gained initial access to the environment, how they maintained persistent remote access once inside the network, and what activities they undertook once inside. Yet with little to no evidence available early on in the response, it is difficult to provide the answers the client is looking for.

Attack: the best form of defence?

To solve this problem, we experimented throughout 2023 by adding members of our Offensive Security practice to our Incident Response teams on complex cases. The task was clear: use the specialist skills of our Offensive Security team to improve our output firstly, by leveraging the unique tools and scripts owned or developed by our Offensive Security team, which might produce different results to the tools used by our Incident Response team; and secondly, by thinking like a hacker to alter how the team approached the response in general.

On the surface, this approach may not appear entirely novel: cyber security teams have been merging blue and red under the banner of ‘purple teams’ for years, but this has been purely for proactive services (i.e adding incident response personnel to offensive security teams for enhanced proactive services). What we were attempting was to improve our reactive services by including red team members in our Cyber Incident Response practice.

So, do we improve our incident response service by including members from both our red and blue teams?

The simple answer was: yes.

The incident

On 16 August 2023, we were brought in to help a major global manufacturer headquartered in the Netherlands, who had been victim of a ransomware attack by the prolific ransomware group known as Lockbit or Lockbit 3.0. Predictably for a business of this size and profile, it was a sprawling corporate network with more than 1,000 servers confirmed impacted. The immediate questions from the Client were straightforward to ask but not to answer: How did Lockbit manage to get into the network? And what data did they steal?

Traditional incident response might involve collecting triage data from all 1,000+ encrypted servers, analyse them, painstakingly tracking down the threat actor – device by device – until the earliest activity is found and, ideally, the point of entry. However, with so many devices and such little time, this solution would be both too expensive, and would take too long to produce actionable insights.

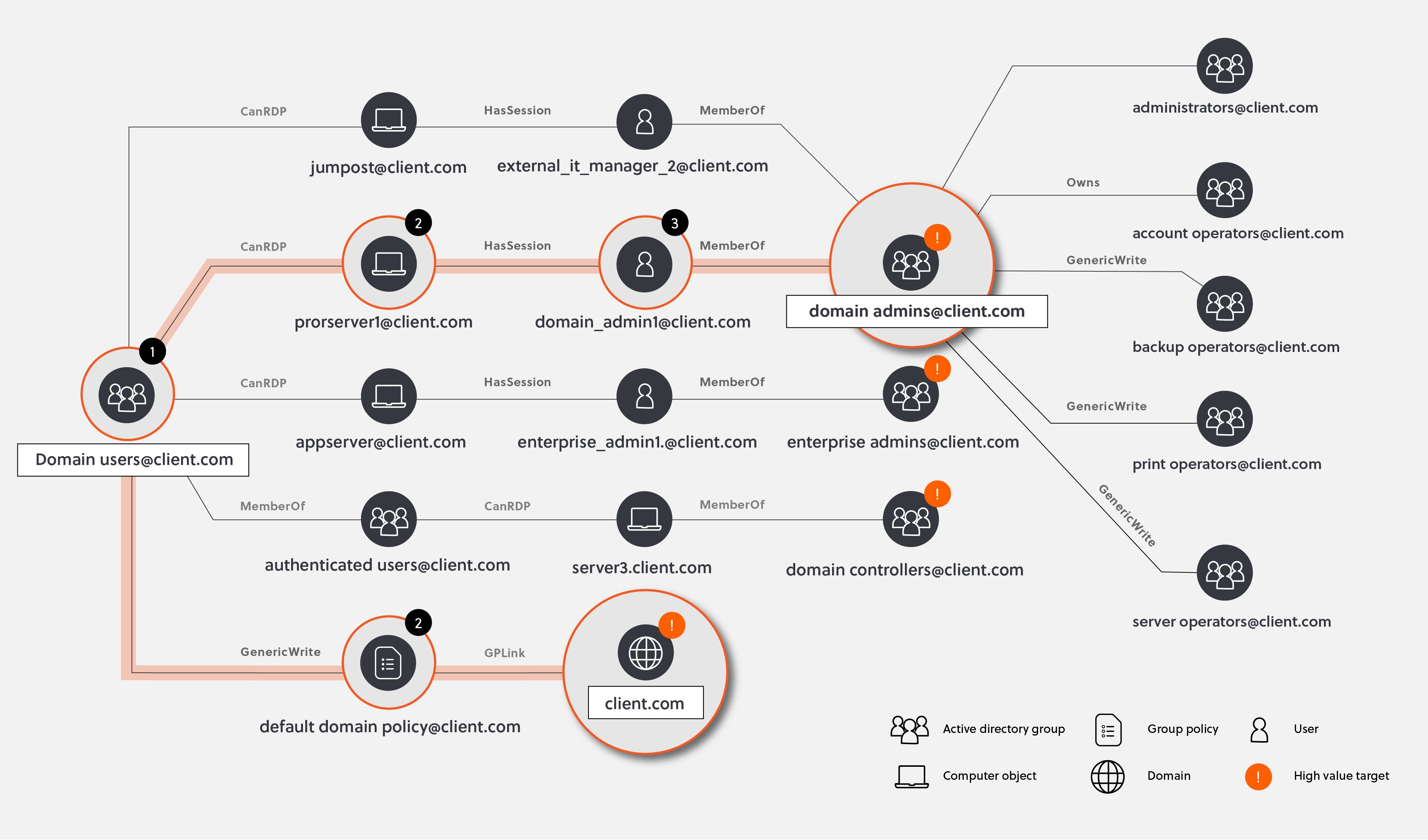

Instead of tracing activity back to the first malicious event, we took a different approach and attempted to answer a different question – what routes would you decide to take to get to the ‘crown jewels’ of the network if you were the hacker? To answer that question, we used a toolkit typically favoured by threat actors and penetration testers, but not a toolkit frequented by traditional incident response teams. Our team ran SharpHound, Ping Castle and Purple Knight to produce a comprehensive view of the vulnerabilities, misconfigurations and insecure aspects of the network, in a similar process to the reconnaissance phase of the attack all threat actors go through.

Find paths, follow footsteps

The results were outstanding. By adopting the mindset and toolset of the Lockbit threat actor at play here, we were able to immediately see the pathways from an impacted device to the domain controllers using an account we knew to be compromised. This attack pathway was one of dozens of the tools flagged, however, it was clearly the route of least resistance – and knowing how a hacker thinks – we knew this would have been the first route they attempted to exploit.

Within hours of beginning rapid forensics on a small subset of the affected server estate flagged by our Pentesting toolkit, we managed to follow the footsteps down this path and confirm how the threat actor had traversed the environment to get to the domain controllers, the accounts used to do so, and a small number of devices which ended up including the first device accessed via VPN during the attack, and our initial access point.

Furthermore, the results of the audit helped use a lot with prioritising and tailoring containment actions, such as, which accounts should be reset first, what access shall be removed from users and which computers shall be restricted from the network.