In 2023, hundreds of thousands of US workers from various sectors went on strike to demand higher pay. With some strikes extending months, many workers were eventually successful in securing more favourable contracts. The question now is whether these wins will encourage continued industrial action in 2024, writes Shannon Lorimer.

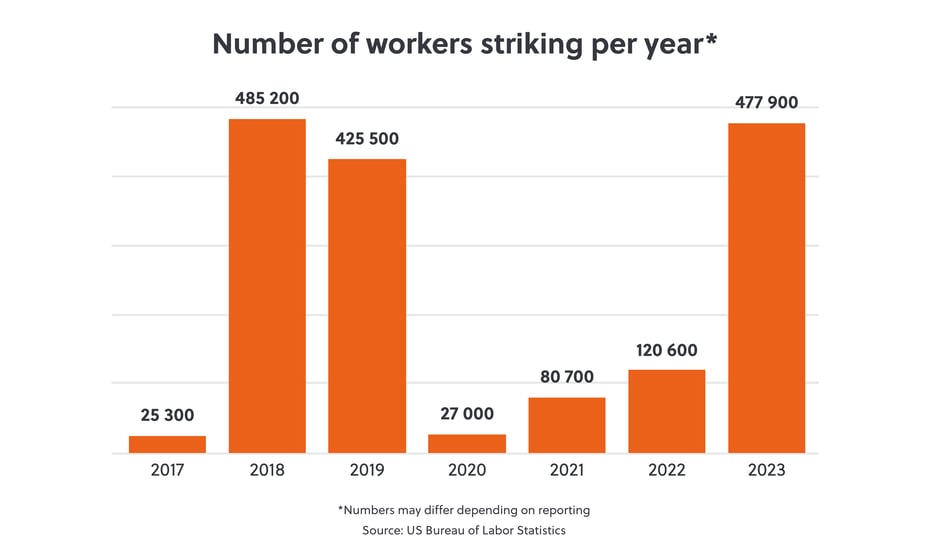

Almost half a million workers in the US went on strike in 2023, making it one of the most prominent years for industrial action since 1990. Though work stoppages in the country have been increasing in recent years, growing frustrations over the increasing cost of living alongside limited wage growth seen over the pandemic – and job market expansion in the US driving an increased confidence to strike – led to a significant increase in worker participation in industrial action in 2023. With many of these factors far from resolved, and in an election year to boot, further industrial action over the next 12 months seems inevitable but will not be without some limitations.

While workers’ motivations to strike have varied between sectors, they have predominantly centred around frustrations over the impact of higher inflation outpacing wage increases in recent years. Despite the US economy expanding and repeatedly defying predictions of a coming recession, the effects of the pandemic-linked inflation peaks in 2021 (7 percent) and 2022 (6.5 percent), which followed several years of muted wage increases, has meant consumers are still feeling the pinch; in fact, workers’ wages are only projected to recover the loss of their purchasing power relative to pre-pandemic levels in the fourth quarter of 2024. Such pressures are likely to have been forefront of many workers’ concerns over the past year. But, as of late 2023, an increasing number of studies show that most workers are earning more today, in inflation-adjusted terms, than they were one year prior, and that wage increases have outpaced inflation 1.15 to 1. As such, grievances over cost of living are unlikely to be the sole reason for further strikes, suggesting that the motivations for industrial action in the US today are far more complex.

The ripple effect of wage deals

In one of the most high-profile strikes in 2023, around tens of thousands of unionised workers affiliated with the United Auto Workers (UAW) group initiated a series of work stoppages to demand increased wages and benefits at the Big Three Detroit automakers. Union representatives negotiated favourable deals for workers, earning around a 25 percent wage increase over four years at all three automakers and cost-of-living adjustments to offset inflation. This success has already unnerved some employers in the broader sector who have pre-emptively increased wages to avoid disruptive and expensive protests – not surprising given that the UAW protests cost automakers around USD 3.6 billion in combined lost profit. Similarly, unionised healthcare workers secured a 21 percent wage increase in their contract after 75,000 members went on a three-day strike in October in the critical sector. Such historical wins are likely to encourage other unions, across sectors, to follow suit, with an emboldened workforce potentially more confident in downing tools.

That being said, the sheer size of the UAW strike was a key contributor to 2023’s standout figures. And the fact that large union contracts that cover some 1.1 million workers are due to end this year may point to similar industrial action levels in 2024. Yet given that those facing contract renewals sit primarily in sectors with severe restrictions on industrial action, including the postal services and rail sectors, associated industrial action will likely be far more muted this time round unless workers are afforded greater collective bargaining opportunities.

Workers gain an upper hand?

US unemployment rates have been declining for several years but the Covid-19 pandemic triggered a major disruption in the US labor force, with some 50 million people quitting their jobs to seek better employment opportunities in a wave dubbed ‘the great resignation’ of 2022. This move forced the hand of the employer to offer bigger pay raises and bonuses to sway people to stay. At the time, employee retention had become an increasing important consideration for employers, leaving the labour force better positioned to make greater contractual demands.

It could be argued that this dynamic has contributed to the strike activity seen across the country as workers become more confident in making their demands. But on entering 2024, the trend of ‘job hopping’ is reversing. Workers have become more cautious in charting their career paths amid growing global economic uncertainty and employers too have become more hesitant in their decision-making, marked by a wave of hiring slowdowns. While in isolation this is unlikely to completely discourage industrial action in 2024, it could dampen individual workers’ willingness to participate.

A pro-worker and pro-union president

With the US election offering a likely rematch between incumbent US President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump, winning the backing of prominent unions is likely to be on the cards for both candidates. Biden has long been an outspoken supporter of unions, becoming the first US president to join the picket lines during the UAW strike in 2023, and has subsequently received the backing of the union. Eager to shake-off an ‘anti-worker’ legacy, Trump is also courting the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Vying for union support is not necessarily new in the US’s political landscape, but this time round, unions enjoy the momentum of 2023 and could use their newfound popularity among presidential candidates to make bigger demands in 2024. Still, aligning with the presidential candidate of the day will do little to reverse some of the pre-existing limitations around collective bargaining in the country in the coming year, particularly given votes will only be cast in November.

Just another year

Despite the high-profile strikes of 2023, workforce union membership in the US remains firmly around the 10 percent mark, with no real movement from the previous year. In part this is accounted for by a growing overall workforce, which is growing at the same pace or faster than union membership. But there is also a hesitance on workers’ part to join unions, with existing labour legislation providing companies the ability to quash unionisation efforts. With all this in mind, the record industrial action numbers seen in 2023 will not necessarily translate into another standout strike year in 2024. Still, polling consistently shows a growing popularity for union membership and strike action, suggesting strikes are here to stay and will contribute to a new norm of elevated industrial action in the country.