Despite some unrest by incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro’s supporters after his defeat in the October 2022 elections, Brazil’s democratic culture and institutions are helping to prevent a right-wing backlash that many expected would result in an attempted ‘self-coup.’ But socio-political tensions remain high, and Bolsonaro could use these pressure points to mobilise supporters against the incoming administration. Erin Drake and Daniel Lima discuss the recent post-election protests, and potential for further pro-Bolsonaro unrest under the incoming government.

Brazilian voters and the international community witnessed months of fearmongering by Bolsonaro over the country’s allegedly fraudulent electronic voting system, coupled with claims that ‘only God can remove [him] from office,’ and bolstered by calls among his supporters for the military to intervene and aid a ‘self-coup.’ It was somewhat surprising, then, that Bolsonaro’s narrow defeat in the elections produced a more muted response than observers had anticipated. In fact, after Brazil’s electoral court published the results on 31 October — with former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva securing a 50.9 percent victory in the runoff — several state governors and members of Congress allied with Bolsonaro were quick to recognise the legitimacy of the results.

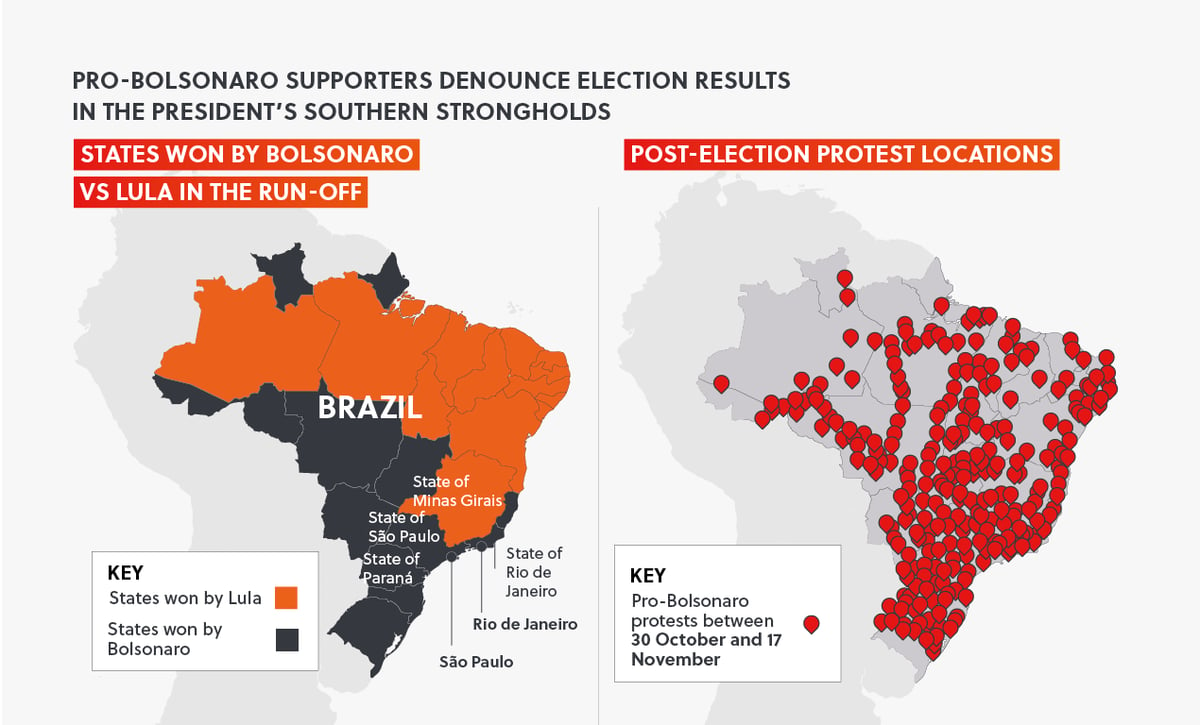

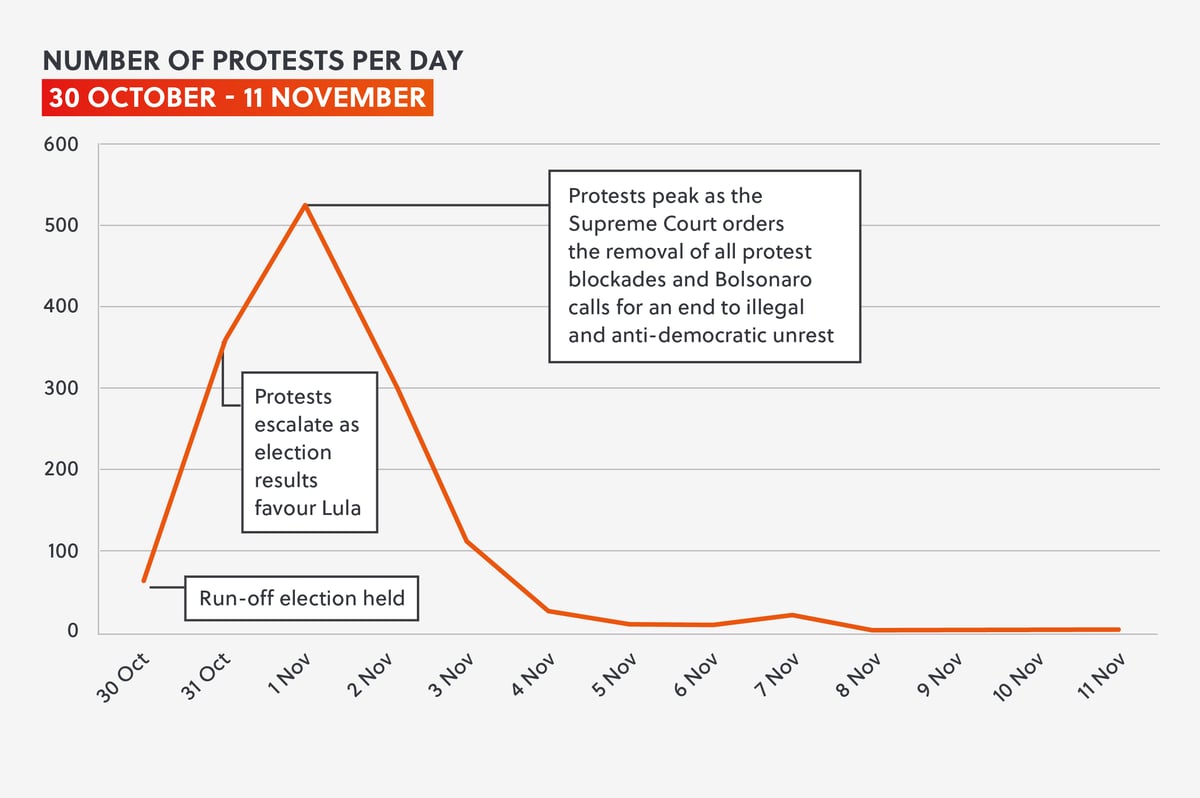

Bolsonaro’s supporters nevertheless displayed dissatisfaction at the outcome, staging disruptive protests in over 20 states, but this backlash quickly lost momentum as the Supreme Court ordered security forces to clear illegal blockades and demonstrations calling for military intervention. Bolsonaro eventually also challenged the results on 22 October, claiming that results from 60 percent of electronic voting machines should be invalidated after his party allegedly found some to have malfunctioned. The Supreme Court overturned this claim and fined the president's party, Partido Liberal (PL), USD 4.3 million for filing a ‘bad faith’ complaint, but his hard-line supporters remain convinced the election was fraudulent and have continued to camp outside military garrisons to demand an intervention. Societal tensions remain high following Bolsonaro’s controversial and politically polarising tenure, and there is strong potential for ongoing and potentially violent incidents of unrest, both during the transition and under the Lula administration.

MIXED SIGNALS

Over 883 protest incidents were reported on 31 October and 1 November alone. Bolsonaro’s supporters blockaded highways and roads, predominantly in southern Brazil. Reports emerged of scuffles between protestors and drivers, and clashes with police tasked with clearing roadways. Unrest prompted supply chain disruptions and affected the availability of medical supplies, food and fertiliser. Supermarkets in several cities, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, reported food shortages. Demonstrators barricaded access to critical grain and meat export ports of Paranagua, Itajaí, and Imbituba, while protesters gathered in front of army barracks demanding intervention.

Most early blockades were demobilised within a week. Bolsonaro’s refrain from openly supporting demonstrations, coupled with his retreat as soon as results began showing Lula’s victory, may have tempered enthusiasm among less hard-line supporters who had probably expected encouragement from the usually vociferous president. Bolsonaro’s public appearance came almost two days after results were published; it was no concession speech, but he indicated that he would respect the constitution. When he later reneged on this promise, with the PL filing a Supreme Court petition in a delayed but mostly unsurprising challenge to the election results, concerns over the long-anticipated potential for a self-coup flared again.

A small but dedicated group of Bolsonaro’s supporters have continued to protest, particularly in Brazil’s agricultural backbone of Mato Grosso State. Police have noted that while the initial post-election protests saw thousands of ad hoc but mostly peaceful roadblocks, those that have emerged in the states of Mato Grosso, Rondônia, Pará, Paraná and Santa Catarina just before the president’s election challenge have been coordinated, carried out at night by hooded men who, when arrested, have been discovered with gasoline canisters, knives, illegal firearms, slingshots, and stones. Commercial trucks belonging to a business tycoon in Mato Grosso who declared support for Lula have been a primary target of arson attacks, and in Sinop, Mato Grosso’s second largest city, pro-Bolsonaro protesters have demanded that businesses and stores close to support their cause, threatening retaliation against those who refuse to comply. Also concerning is the fact that Bolsonaro is reportedly holding discussions with former US president Donald Trump’s aides, who have praised Brazil’s protests and spread conspiracies around the allegedly stolen election.

DRIVERS OF UNREST

Several drivers and developments could prompt an escalation protest action among Bolsonaro’s supporters in the coming months, even if the current unrest dissipates – which seems likely given court orders to clear any blockades and arrest suspects.

Concerned observers have drawn parallels to the January 2021 Capitol Hill riots, highlighting the potential for a pro-Bolsonaro riot during the inauguration. With a high turnout expected among Lula and Bolsonaro supporters in Brasília, tensions may drive rival groups to clash, or Bolsonaro’s supporters to attempt to forcibly occupy government buildings like Congress as they have previously done. A bolstered police presence could also contribute to demonstrations becoming violent, particularly considering the armed individuals operating later roadblocks in Mato Grosso and other Bolsonaro strongholds. Any unrest ahead of the January 2023 inauguration will therefore likely be led by Bolsonaro’s supporters, although he may continue to tacitly encourage such demonstrations.

Bolsonaro’s supporters could also stage protests in the coming years should he stand trial or be charged in relation to pandemic mismanagement, disseminating fake news regarding the outbreak, and other allegations. The threat of prosecution may encourage Bolsonaro to leverage his support base to pressure judicial decision-making through economically crippling unrest. In a country where over 60 percent of goods are transported overland, pro-Bolsonaro supporters — particularly commercial truck drivers, a major constituency who benefit from Bolsonaro’s fuel policies — have often shown willingness to facilitate countrywide disruptions against the Supreme Court and in support of the outgoing president.

Bolsonaro’s tenure was characterised by the president and his supporters’ use of social media to run disinformation campaigns and target rivals, and an associated Supreme Court crackdown on such activities. Further such measures – like the Supreme Court’s suspension of social media accounts of Bolsonaro allies who remain critical of elections – could be a catalyst for unrest in the coming year, particularly if right-wing factions view this crackdown as attempting to silence them or Bolsonaro.

There is also longer-term potential for unrest, both during the transition and under the Lula administration, wherein Bolsonaro could leverage other issues like the socio-economic fallout of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia-Ukraine war to mobilise supporters against the new government. Considering the current global macroeconomic climate, the Lula administration will likely struggle to prioritise spending to maintain an extensive state welfare program, particularly faced with high government debt and concerns over rising inflation. Bolsonaro could exploit such socio-economic pressure points to rally opposition forces and supporters.

BOLSONARO’S LONG GAME?

Bolsonaro’s response to the elections and demonstrations continues to be somewhat mixed and muted, and his next moves are unclear. He has already authorised the transition of power, which at this stage seems to be in motion as Lula’s administration appoints heads of various government portfolios. Yet, the situation remains volatile, and unrest may escalate largely depending on the president’s actions, comments or silence in the coming weeks. However, a few factors will likely continue to limit the potential for a widespread insurrection, a self-coup or military intervention.

"The transition period and inauguration will be the first litmus test for both Bolsonaro and his supporters’ acceptance of the new political ‘normal."

Tables turn: First, Bolsonaro may be avoiding the public eye intentionally as a means of silent encouragement (or a ‘skin condition’ as the Vice President reported). But his silence aside from discouraging illegal protest tactics also suggests acknowledgement of his increasingly precarious position as an outgoing leader who has antagonised powerful institutions and figures like Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who may double-down on investigations against him as presidential immunity falls away. A Senate committee has already recommended charges of ‘crimes against humanity’ over Bolsonaro’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic, while another investigation into his alleged obstruction of justice during a corruption investigation into his son is pending.

Maintaining support: Bolsonaro also still intends to use his considerable political capital to head the PL in Congress, and according to the party’s current leader, run for re-election in 2026. But controversial policies and perceived disrespect for democratic process already cost him this election, and actively encouraging further protests could compromise his position or alienate his wider support base, hindering his ability to leverage his popularity.

Deep-seated democracy: While not completely insulated from political machinations, democratic culture remains entrenched in Brazil’s institutions like the Electoral and Supreme Courts. Both courts are highly respected and have functioned as an effective bulwark against Bolsonaro’s more threatening initiatives like disinformation campaigns, limiting indigenous rights and suppressing academic freedoms. The Supreme Court, for example, sent a strong message on 1 November that anti-democratic rhetoric and actions would not be tolerated, ordering a police crackdown on illegal blockades, fining truck drivers and freezing accounts of 43 individuals and companies driving anti-democratic demonstrations. This underlying ideological and institutional support for a democratic system will continue to limit opportunities for a self-coup or insurrection, even though unrest remains likely.

ON A KNIFE’S EDGE

The trajectory of Brazilian politics and Bolsonaro’s decision-making over the coming months is uncertain. Some active and senior members of the military have come out in support of the president, even though the institution – which suffered reputational damage under Bolsonaro and has frequently been drawn into the ‘self-coup’ rhetoric among the president’s supporters – proved its commitment to democratic order, remaining mostly impartial amid protests outside their barracks. They further reinforced the legitimacy of the electoral process in an independent audit initially called for by Bolsonaro, likely in the hope that the institution would support his claims of fraud in the electronic ballot system. Further, public appetite for violence and self-coups is low and even some of Bolsonaro’s political allies have called his bid to overturn election results absurd and dangerous.

The transition period and inauguration will be the first litmus test for both Bolsonaro and his supporters’ acceptance of the new political ‘normal,’ while the months after will likely see the former leader continue his efforts to promote a conservative agenda. Certainty comes in the knowledge that Bolsonaro will retain significant influence over the political and social spheres, and while a coup is unlikely, this influence will sustain the threat of disruptive opposition-led protests.

Email Erin

Email Erin

@SRMInform

@SRMInform

S-RM

S-RM

hello@s-rminform.com

hello@s-rminform.com