As President Daniel Noboa follows a path of militarising Ecuador’s response to violent organised crime, Tamsin Hunt explores the challenges in this approach, and in finding longer term solutions to gang-driven insecurity.

Five years ago, Ecuador was considered one of the safest countries in Latin America. Today, its security situation is spiralling; criminal gangs run riot in prisons, and stage bombings and political assassinations with near impunity. In response to this worsening environment, newly elected President Daniel Noboa had campaigned to address the security crisis through social and institutional reforms. His response in practice, however, has entailed more of a military crackdown. His declaration of war on the gangs in the country set in motion a violent response that has left the country reeling. In early January 2024, 19 people were killed and more than 150 guards were taken hostage in violent riots at several prisons, while in the port city of Guayaquil, heavily-armed criminals stormed a television station during a live broadcast. On 8 January, Noboa declared a 60-day state of emergency (later extended by a further 30 days), deployed armed forces to affected areas and designated 22 criminal groups as terrorist organisations. Now, while this approach has seen some immediate success, and Noboa has seen his own popularity grow, it is less clear whether this response will enjoy long-term success.

Imported turf wars

For decades, Ecuador’s strategic location along drug transit routes has made it a hub for the regional and global drug trade. More recently, however, the growing global demand for cocaine, alongside the proliferation of new synthetic drugs like fentanyl, have driven powerful cartels from neighbouring countries like Mexico and Brazil to search for new transit routes to circumvent authorities and accommodate rising volumes of illicit cargo. As a consequence, the expansion of both transnational and domestic gangs into Ecuador has led to rising insecurity in the country. Associated gang rivalries and turf wars, particularly in cities along key transit routes like Guayaquil, have since burgeoned, culminating in the extreme violence witnessed in the first few months of 2024.

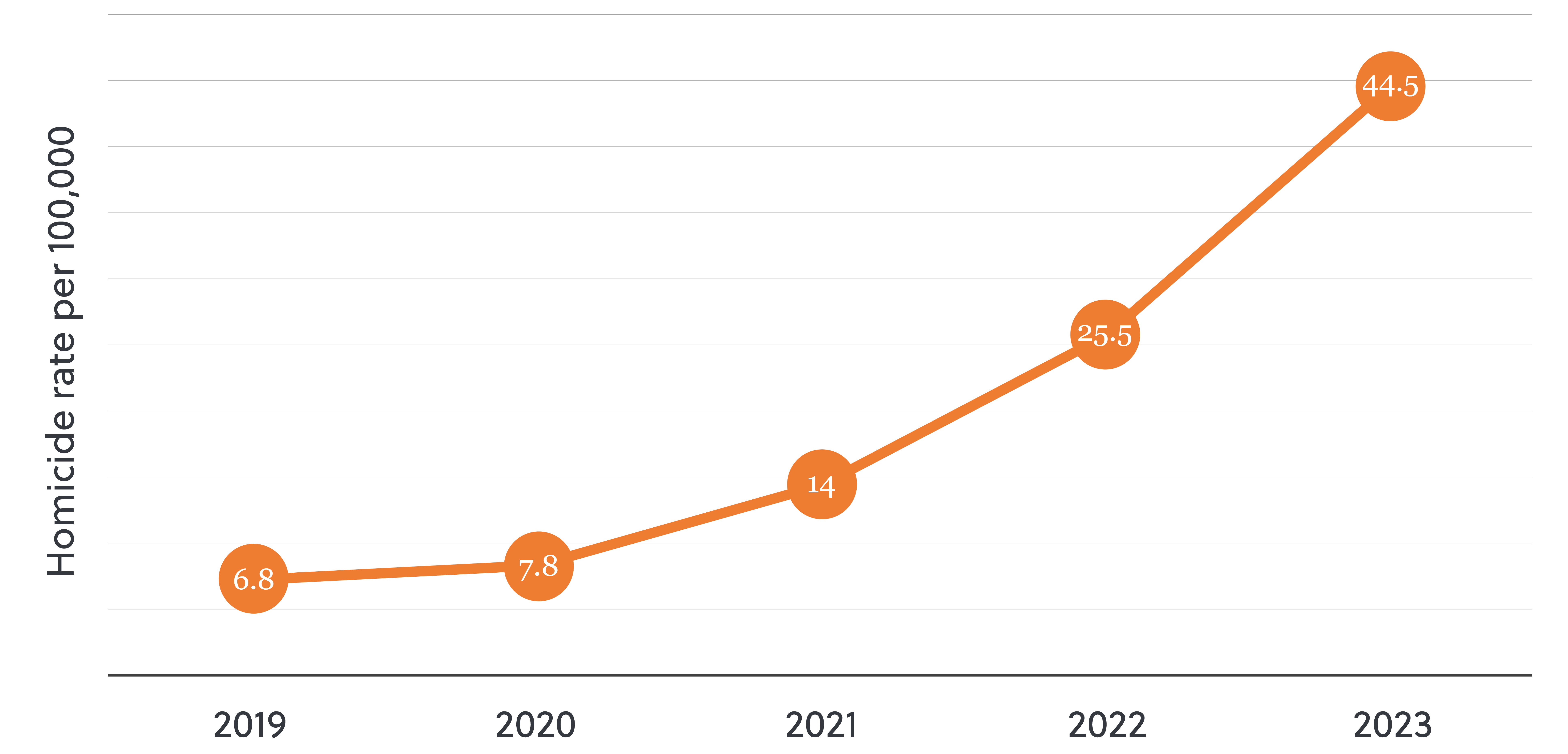

Ecuador’s homicide rate per 100,000 over the past five years

Data sourced from Insight Crime, a think tank specialised in organised crime in Latin America, and the World Bank

Systemic challenges

At the same time, Ecuador’s institutional environment has deteriorated over successive administrations, weakened by a series of policy decisions that defunded security services, weakened the judiciary, and disrupted the ability of local governments to supply even basic services like sewerage, water and electricity, further opening avenues for criminalisation. Ecuador has also experienced deteriorating socio-economic conditions, with high levels of poverty and unemployment – worsened during the Covid-19-related lockdowns – that have provided a rich source of dissatisfied and disenfranchised youth for gang recruitment. Meanwhile, corruption has allowed organised crime to flourish in Ecuador’s prison system, from where gangs comfortably orchestrate many of their operations - and clash violently over control and access to resources.

Improvement at a cost

On the face of it, Noboa’s militarisation strategy since he came into office in November 2023 has proven somewhat effective – in fact, Police Commander César Zapata claims that with the state of emergency in place, violent deaths decreased countrywide by 17 percent between early January and early March 2024. Given this success, a national referendum scheduled for 21 April – intended to gauge public appetite for granting robust powers to the armed forces, among other initiatives – is likely to be successful and may lend more legitimacy for Noboa’s current approach.

However, this success has already come with consequences for civilian safety. The January hostage situation is a case in point as too is the recent assassination of the 27-year-old mayor of San Vicente in March 2024. In the coming months, Noboa is set to face significant resistance from the gangs, who are not only eager to hold their ground but are also intent on securing access to profitable drug-trafficking corridors. It is likely to be a long battle ahead and it is unclear if the government has the funding to sustain a prolonged military deployment and the requisite enhanced security measures. In fact, the country is already facing ongoing budgetary challenges and the cost of troop upkeep alone is estimated to be around USD 1 billion in 2024.

Without a balanced strategy that also involves addressing the root causes of organised crime, Noboa risks setting Ecuador on a path that may rely increasingly on states of emergency and military interventions at the expense of lasting peace.”

Cyclical violence?

With these challenges already present, the question remains over whether these measures can make a long-term impact. Despite Noboa’s well-intended campaign promises to address corruption, social issues and inequality, this is admittedly harder to achieve in practice, particularly in the face of such immediate threats of widespread violence. And, gangs in Latin America have shown an enduring ability to adapt to such crackdowns. Without a balanced strategy that also involves addressing the root causes of organised crime, Noboa risks setting Ecuador on a path that may rely increasingly on states of emergency and military interventions at the expense of lasting peace.