On 8 April, Zimbabwe officially began trading its new currency, the Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG). The new governor of the central bank, John Mushayavanhu, revealed the new tender – which is backed by a basket of precious metals and foreign currency reserves – during his first monetary policy statement since his appointment at the start of April.

The ZiG will replace the Zimbabwean dollar (ZWL), which has been among the world’s worst-performing currencies having lost more than 70 percent of its value since the beginning of 2024 alone. At the time of its demise, the ZWL was trading at around ZWL 30,671 per USD 1, a far cry from the ZWL 2.5 per USD 1 when it was first introduced in 2019.

The central bank set the new currency’s introductory exchange rate at ZiG 13.56 per USD 1, with USD 100 million in cash and 2,522 kilograms of gold (worth USD 185 million) backing it. The ZiG will be allowed to float freely. The USD – which is used for more than 80 percent of transactions in Zimbabwe – will continue to be permitted as a legal means of exchange, maintaining the existing multi-currency system. However, to harness demand for the new notes, authorities will implement a mandatory requirement for companies to settle at least half of their tax obligations in the ZiG. The shares of all companies listed on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange (ZSE) will also now be denominated in the ZiG, with all ZSE indices rebased to 100 basis points. Although the ZiG’s value strengthened slightly in its early days, the adoption of the new system has already got off to a rocky start. With many banking systems offline as they work to transition to the ZiG, people have been left stranded with the old ZWL, as some businesses and transport operators are already refusing it, despite it remaining legal tender until 30 April.

Sixth time lucky?

This is Zimbabwe’s sixth attempt to create a new currency system since 2009. In that year, the government introduced a multi-currency system to try and stabilise the economy amid unprecedented hyperinflation. Since then, Zimbabwe has gone back and forth between a multi- and single-currency system, adopting several versions of the Zimbabwean Dollar (ZWD and ZWL) and introducing the use of gold coins, known as Mosi-oa-Tunya. Each of these systems has failed to stabilise prices and curtail exchange rate volatility, and the government’s excessive printing of currency to fund growing expenditures has contributed to the depreciation of the local units.

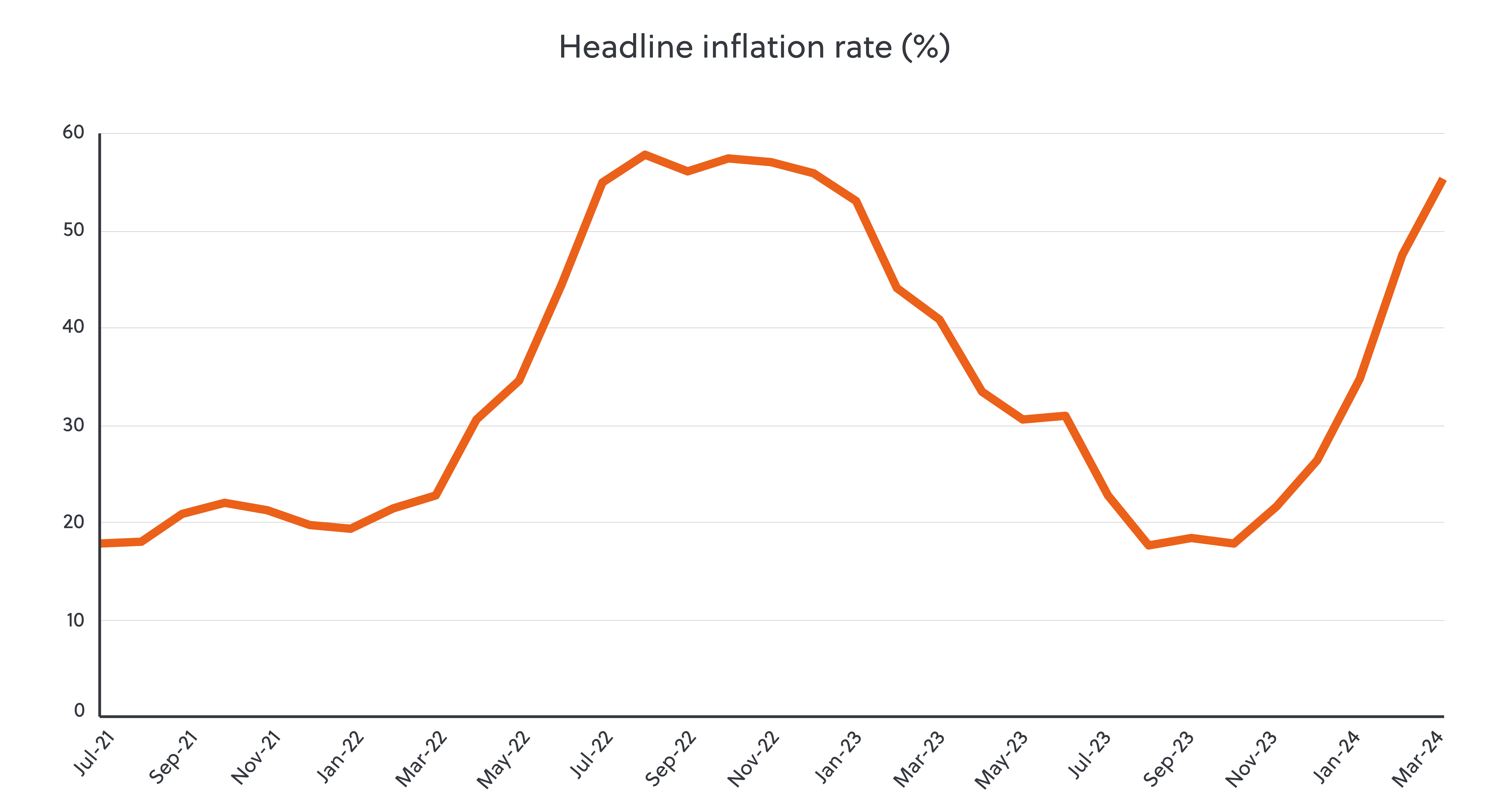

The population has borne the brunt of this crippled economic system, which has eroded their savings and purchasing power – in March, the country slipped into hyperinflation territory once again, with CPI inflation reaching 55.3 percent, up from 47.6 percent a month prior (see Figure 1). According to the latest data from the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 42 percent of the population were living in extreme poverty in 2022, and this figure remains elevated amid persistent inflation since then. In this context, the government’s promise that the new currency will facilitate macroeconomic stability rings hollow.

Figure 1: Zimbabwe’s economy has been impacted by pronounced price volatility

More of the same…

Public distrust, driven by decades of economic mismanagement, has adversely affected the credibility of a local currency system, regardless of the currency of the day. With the new central bank governor being a member of President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s ‘inner circle’, monetary policy remains vulnerable to meddling and manipulation by the government, and his optimism over the ZiG will do little to appease the people. Should a lack of real political will continue to impede monetary and foreign exchange reforms, the ZiG risks becoming just another damp squib. Whether it’s the ZiG, the buck or gold itself, without a new degree of fiscal discipline to boost confidence among businesses and international investors alike currency risks in Zimbabwe will be here to stay.