Amid a new wave of kidnapping in the Philippines, Tamsin Hunt investigates recent trends; looking at the prime targets and perpetrators, and where, why and how incidents manifest.

Kidnapped on 19 July, a pharmaceutical businessman was last seen near his residence in Taguig, Manila, when he collected almost USD 100,000 in cash and two expensive watches from his personal assistant. His burned body was later found in Santo Tomas, Batangas on 8 August; although his kidnappers continued to demand a ransom of almost USD 2 million from his family up until 1 September. Authorities have laid charges against eleven people, but the brain of the operation, allegedly a casino card dealer from Santo Tomas, remains at large.

There has been an alarming rise in kidnappings in the Philippines over 2022, according to the Movement for the Restoration of Peace and Order (MRPO), an organisation set up in 1993 to combat kidnappings. The MRPO estimates that between 40-48 kidnappings have taken place to date in 2022, the highest since 2019 when 85 cases were reported. The dip in kidnappings during the intervening years (33 in 2020 and 38 in 2021) have been attributed to Covid-19 and related government lockdowns. Meanwhile, the Philippine National Police (PNP) have downplayed the recent wave, claiming that reported increases were nothing more than ‘crime hype’ and ‘fake news’. According to the PNP, only 27 kidnapping incidents have been reported to the police to date in 2022, supposedly down from 2021.

Of those 27 cases reported to police, roughly half have been related to the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operation (POGO) industry, often targeting Chinese nationals. Gambling is illegal in China and considered an immoral activity, and so hundreds of thousands of Chinese nationals look to the Philippines for gambling, as well as employment in the sector. The motives behind the remaining reported incidents range from financial gain to human trafficking, but kidnappings frequently go unreported, and many victims refuse to cooperate with authorities.

While, by its very nature, the kidnapping business and related statistics are opaque, below we highlight some key features of the kidnapping landscape in the Philippines.

Kidnapping in the Philippines: Who, where, why and for how much?

VICTIM PROFILES

VICTIM PROFILES

Victims are most commonly Chinese, Cambodian, Vietnamese and Malaysian nationals because of their perceived wealth, and, according to the MRPO, women are often targeted over men, as they are seen as ‘more manageable’. Gamblers and casino workers are often kidnapped either because of perceived wealth, or due to accumulated debts.

LOCATIONS

LOCATIONS

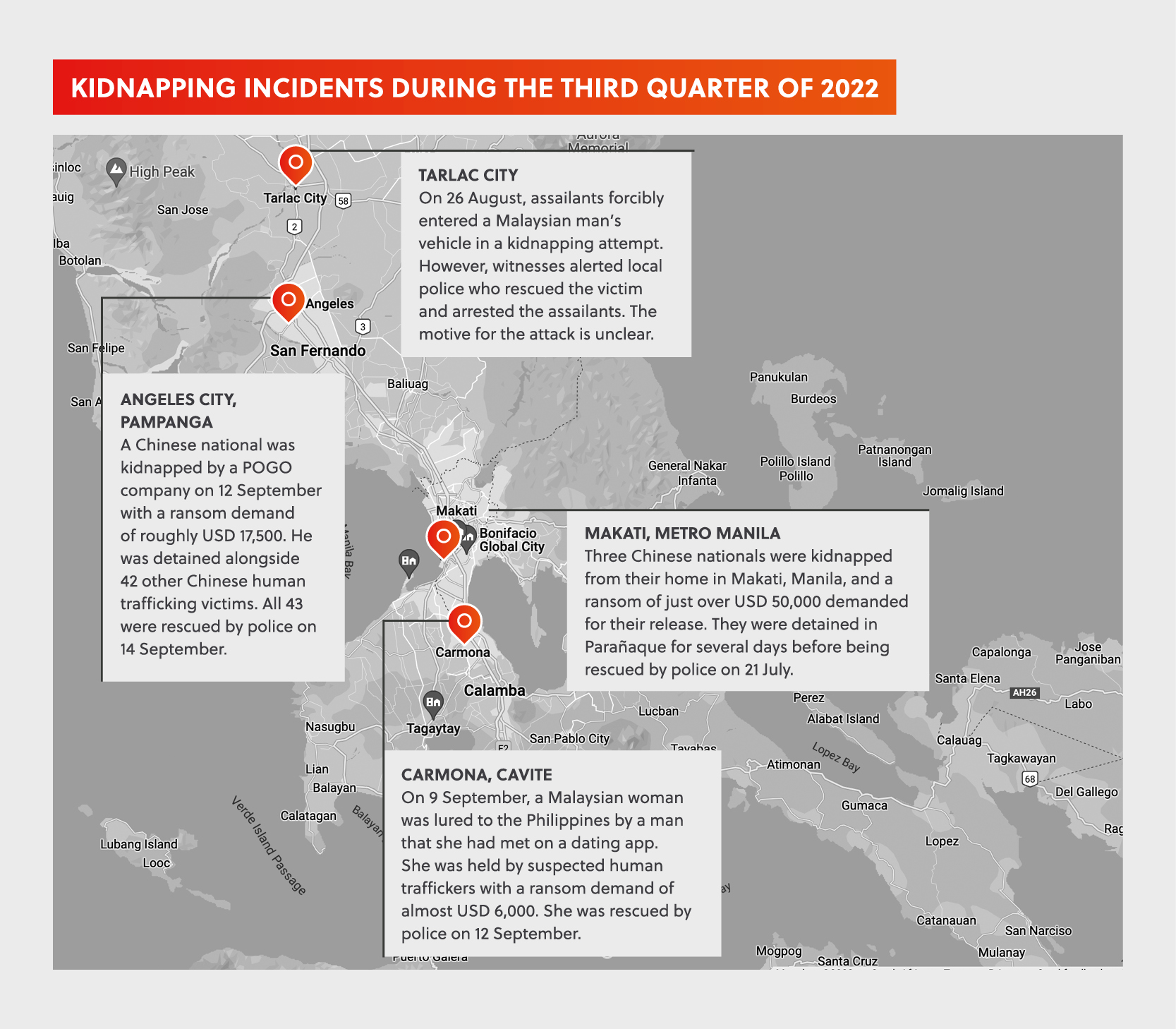

Kidnappings take place across the Philippines, but most recent hotspots are in and around Manila.

KIDNAPPER PROFILES

KIDNAPPER PROFILES

Kidnappers are often members of organised criminal gangs and gambling syndicates that are part of the POGO industry. Some POGO syndicates moved to the Philippines after Cambodia cracked down on gambling and organised crime, banning online gambling in August 2019.

RANSOM DEMANDS

RANSOM DEMANDS

Recent ransom demands have ranged from USD 6,000 to USD 2 million. The largest ransom payment in the Philippines amounted to USD 7.3 million in the 1990s, paid by a POGO operator for his son who had been held hostage for several months. Previously, payments were made through legitimate Chinese banks, but are now more commonly made through black market remittance centres due to strict government policies on money laundering and remittances.

Abu Sayyaf

The Philippines has been, in the past, dubbed as the kidnapping capital of the world, mostly due to the Islamist militant group Abu Sayyaf, who were responsible for hundreds of kidnappings from the early 2000s to the late-2010s, using kidnap for ransom as a means of raising funds. The group still operates out of the Southern Philippines, but decades of infighting and police operations have depleted their strength and resources, and they are now estimated to be limited to 200 armed fighters. Although no western nationals have reportedly been kidnapped in recent years, Abu Sayyaf remain a significant security threat in the region.