Mozambique’s elections have long been characterised by periods of post-election unrest and violence. In 2024, however, we have seen a substantive shift in the country’s political environment, as the public increasingly becomes dissatisfied with the longstanding status quo, writes Tamsin Hunt.

Political unrest has engulfed Mozambique in the weeks since the country held presidential elections on 9 October. In the capital city, Maputo, opposition supporters set fires and barricaded roads, while the police and military responded with tear gas and rubber bullets. Six weeks after the polls, the death toll stood at 50, with hundreds more injured, while opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane continued to demand a recount of the vote.

Post-election unrest is nothing new in a country considered to be one of the poorest in Africa, and where the ruling party, Frente de Libertaçao de Moçambique (FRELIMO), has regularly been accused of largescale corruption and election fraud. This time round, however, socio-economic grievances have deepened, and political dynamics have shifted, posing significant challenges for the newly elected administration led by FRELIMO's Daniel Chapo.

Political mistrust and economic deterioration

FRELIMO has governed Mozambique since the country’s independence in 1975, and since it became a multi-party democracy in 1992, but the party is yet to hold a single election considered to be free and fair by the opposition or independent observers. Although FRELIMO won the latest election with a comfortable majority of 70 percent, corruption is endemic and institutionalised, and elections are plagued by accusations of largescale voter fraud and intimidation. Furthermore, Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO), Mozambique’s longtime opposition, has lost the public’s confidence as an effective opposition; its reputation particularly weakened by a controversial deal in 2018 to decentralise government, which was widely perceived as collaboration between the two longtime foes. Indicative of growing discontent with the political status quo, only 43 percent of eligible voters took part in the election, down from the 52 percent that participated in 2019. Meanwhile, RENAMO’s share of the vote dropped from 22 percent in 2019, to only six in 2024, with most of that mandate transferred to the emergent opposition party, Partido Optimista pelo Desenvolvimento de Moçambique (PODEMOS).

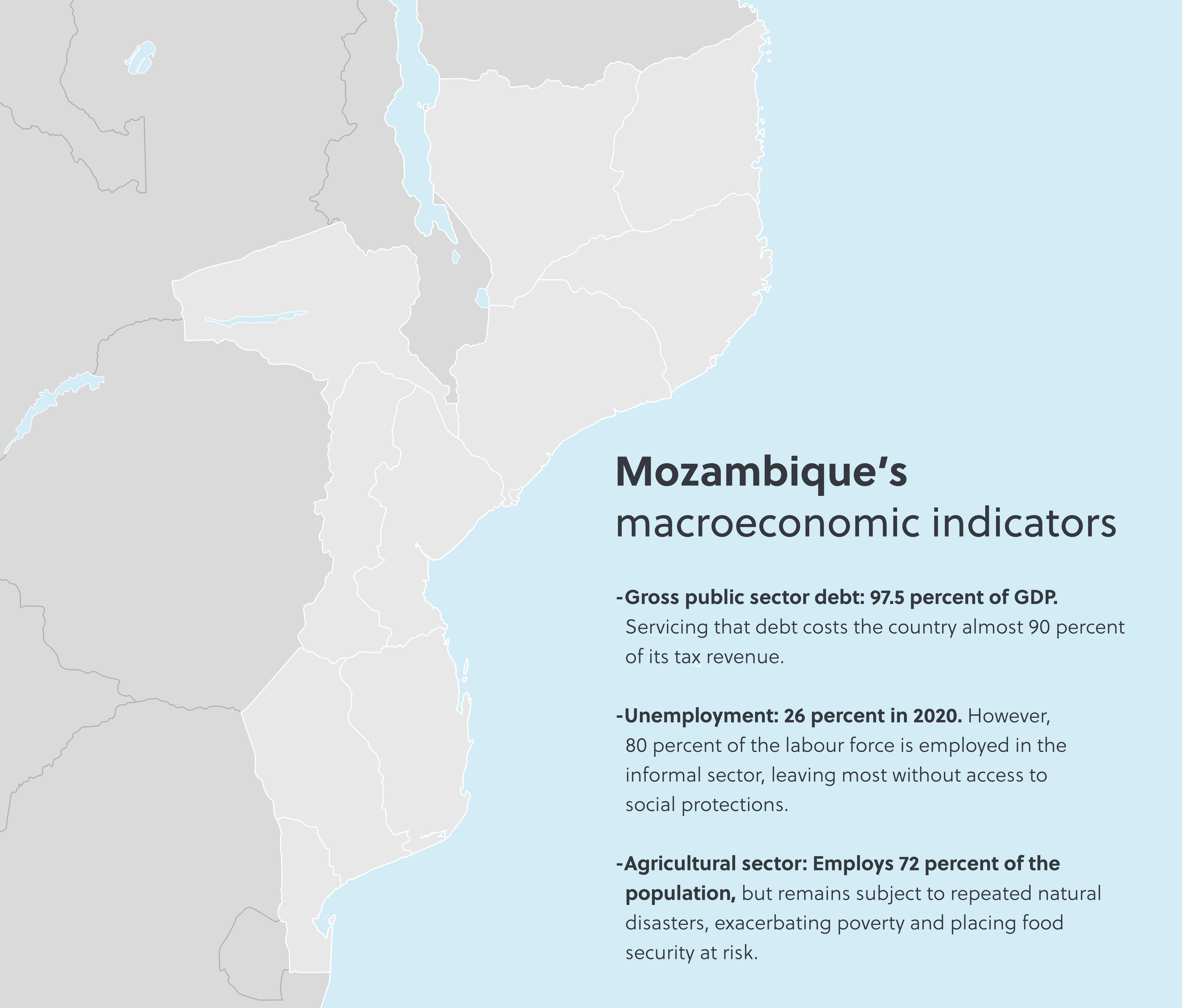

Years of endemic corruption and economic mismanagement have also had a pervasive effect on everyday life in Mozambique. The 2016 hidden debt scandal – where undisclosed government debt worth a staggering 12 percent of the country’s GDP came to light – left the country in dire fiscal straits, and the consequences continue to be felt to this day. According to government statistics, 65 percent of Mozambique’s population lives below the poverty line, although these numbers increase in rural areas, compared to urban, and in the north, comparative to the south. Lengthy power outages are common, roads have fallen into disrepair, and few citizens have access to adequate healthcare, education, water or sanitation, as government has been forced to cut back on public spending. Despite rich reserves of natural resources, and an extractives-driven economy that promises to grow by between four and five percent in 2024 and 2025, the government is largely unable to capitalise on that growth. Not only will corruption and economic mismanagement continue to restrict government efforts in delivering basic services and reducing poverty, but it also renders it largely incapable of coping with shocks, both external and domestic, whether it be the Covid-19 pandemic, destructive climate events, or the ongoing insurgency in the north.

![]()

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Bank, African Development Bank

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Bank, African Development Bank

Conflict to the north

Mozambique’s northernmost Cabo Delgado Province – a region rich in liquified natural gas and mineral resources – has been the scene of a largescale insurrection since 2017. The insurgency is driven by Islamist extremist group, Islamic State Mozambique (ISM), seeking to establish an independent state, but it is rooted in the region’s disenfranchised youth, deeply aggrieved by years of socio-economic neglect, and exclusion from the benefits of vast, multinational LNG projects. Government efforts – bolstered by foreign troops from Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries and elsewhere – to quell the conflict have fallen short. SADC forces achieved a measure of stability between 2021 and 2024; however, after years of insufficient funding, ineffective coordination and disputes with the Mozambiquan government, its forces began to withdraw between April and July 2024. Violent attacks quickly resurged, with civilian casualties increasing by 300 percent in the first half of 2024, compared to the preceding period. Meanwhile, multinational LNG projects are increasingly reliant on foreign security, particularly the measure of stability brought by thousands of Rwandan troops deployed to areas around the projects since 2021.

![]()

Source: World Bank and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

Source: World Bank and UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

A shift in the status quo

Newly elected President Daniel Chapo – a relatively unknown political candidate before FRELIMO put him forward as its candidate – will have his hands full trying to stem the insurgency in the north, reduce poverty and root out corruption. His promises, however, have been met with scepticism, with Chapo himself catapulted to office by a party accused of widespread corruption and election fraud at scale. Meanwhile, the loss of political credibility – of both FRELIMO and RENAMO – and deepening socio-economic issues has given power to a new political element, PODEMOS, led by Venâncio Mondlane. How PODEMOS plans to leverage its newfound political status as main opposition remains to be seen, but one thing is certain, Mozambique’s disenfranchised public are nearing a tipping point. Without substantive change in this next administration, we will likely see continued cycles of unrest and political violence in the years to come.