The ongoing conflict in Gaza has expanded beyond the Palestinian Territories, Israel, and southern Lebanon, with its reverberations being felt in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere. Tamsin Hunt explores some of the ways in which current hostilities could be the catalyst for greater escalation in the region.

In a region where conflicts echo far beyond their origins, the ongoing war in Gaza is increasingly complicating the Middle East’s security landscape. Amid rising regional tensions, ceasefire proposals continue to pass back and forth between Israel and Hamas, with US, Qatari, and Egyptian mediators working tirelessly to broker an agreement. The journey towards a lasting ceasefire and a subsequent agreement on the future governance of Gaza is fraught with challenges, primarily due to the starkly contrasting positions of Israel and Hamas. For example, Hamas insists on the withdrawal of Israeli troops from Gaza, while Israel rejects any scenario in which Hamas maintains any degree of authority in a future Gaza.

Haunted by the gravity and scale of the 7 October Hamas attack and the need to reestablish national security, Israel continues to conduct the Gaza offensive in a manner that has attracted considerable international criticism. This has partly contributed to unprecedented hostilities spreading outward, with Iran’s so-called ‘Axis of Resistance’ – a wide network of political and militia alliances – leading the response against Israel and its main backer, the US. Their actions, and retaliation from Israel and the US, have manifested as tit-for-tat attacks in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Yemen and the Red Sea, coming dangerously close to triggering open conflict in recent weeks.

Regardless of how events unfold in Gaza, recent developments appear to have destabilised the regional equilibrium, suggesting a move towards greater volatility and unpredictability in the Middle East.

Hezbollah and the cycle of aggression

One of the most prominent and powerful groups in the Iran-backed alliance is the Lebanon-based Shi’a movement Hezbollah. After Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October, Hezbollah initiated an attack on the disputed Shebaa Farms area controlled by Israel, triggering daily cross-border exchanges that continue to this day. At times, attacks have come close to escalating into a wider conflict, such as on 14 February, when a Hezbollah rocket attack killed one Israeli soldier in Safed, northern Israel, prompting Israeli retaliation that killed 15 people in southern Lebanon.

Hezbollah by all indications wants to avoid full-scale conflict, wary of severe Israeli reprisals that could surpass the costly impact of the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war. However, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, has warned on multiple occasions that the group’s cross-border shelling into Israel will continue until there is a ceasefire in Gaza. Israeli officials have also persistently warned against ongoing instability at the northern border, citing widespread property damage and the displacement of 80,000 residents due to Hezbollah rocket attacks. An escalation in Israeli strikes against Hezbollah could provoke reciprocal actions, significantly increasing the risk of a major conflict. Even if there is a ceasefire in Gaza or some type of agreement between Israel and Hezbollah, the current crisis has demonstrated Hezbollah’s readiness to engage with or respond to Israeli attacks at a level not witnessed since 2006, highlighting a long-term security concern for Israeli and Lebanese policymakers.

Houthis in Yemen: The surprise element

If Hezbollah entering the fray was predictable, the Houthis firing rockets towards southern Israel and attacking Israel-linked and other commercial vessels in the Red Sea took many by surprise. Several major shipping operators have suspended operations through the Red Sea corridor over security concerns. The Houthis view their response to the Gaza conflict as advantageous both within Yemen and in the broader region. Domestically, they are capitalising on widespread Yemeni support for the Palestinian cause to bolster their support base, while regionally, their actions in the Red Sea elevate their status within Iran’s extended militia network.

These factors likely explain why, in spite of regular US and UK strikes on Houthi military assets in Yemen, the group continues to target merchant vessels in the Red Sea. Like Hezbollah, the Houthis have vowed to maintain attacks until there is a ceasefire in Gaza. Even if there is a ceasefire, their recent actions underscore the significant risks posed by non-state actors possessing state-like capabilities to disrupt international shipping. It is plausible that the Houthis will launch similar attacks in the future, potentially leveraging these tactics in the context of the Yemeni civil war or other regional conflicts.

Militias in Iraq and Syria: The committed partisans

The final element in Iran’s proxy network consists of multiple armed militia groups in Iraq and Syria. These groups began attacking US troops and assets in Iraq and Syria in November 2023, primarily in response to US support for Israel, although they too have strategic interests at play, such as driving US troops out of the region. While the US has intercepted the vast majority of these attacks, one drone breached its defences on 28 January, killing three US soldiers at the Tower 22 US base in north-east Jordan. In immediate efforts to walk back the escalation, Katai’b Hezbollah, one of the most prominent militias in Iraq, suspended attacks on US targets. But the US naturally retaliated, prompting Katai’b Hezbollah to threaten to resume attacks until US forces are “expelled from [Iraq].” These developments have shown that, independent of the Gaza situation, these groups possess both the determination and ability to strike US interests in the region, which they may exercise again in the near future.

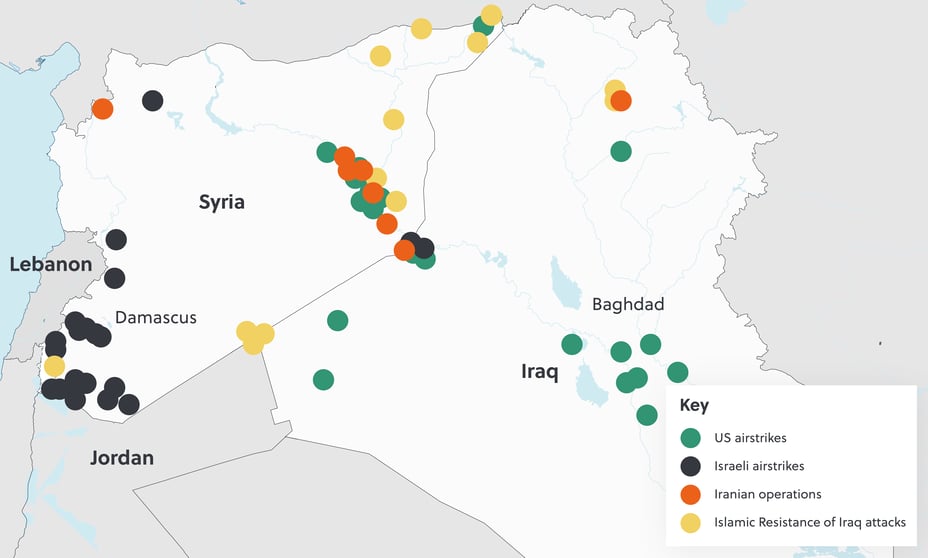

Figure 1: Locations of airstrikes and rocket attacks, and the actors responsible, in Iraq and Syria, 7 October 2023 - 7 February 2024. Data source: The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

Iran: Caught between a rock and a hard place

Iran has long demonstrated its wariness about engaging in direct conflict against Israel or the US, rather using its non-state allies in asymmetric warfare, which allows it a level of plausible deniability. However, these proxies operate with varying degrees of autonomy, pursuing their own interests which may not always align with Tehran’s strategic goals. Should these groups overstep or be perceived as directly threatening US or Israeli interests, Iran will find itself directly accused. For example, the attack on Tower 22 in Jordan, potentially linked to Iranian-backed groups, prompted fears that the US would carry out strikes on Iranian territory or Iranian military personnel and assets in the region. The complexity of managing these proxy relationships, coupled with the potential for miscalculation, leaves Iran in a precarious position. In this high-stakes environment, Iran’s challenge in the coming months will be to navigate these pressures without triggering a wider regional conflict – a task that has become more difficult than at any other time over the past decade.

In this high-stakes environment, Iran’s challenge in the coming months will be to navigate these pressures without triggering a wider regional conflict – a task that has become more difficult than at any other time over the past decade."

US foreign policy challenges in the Middle East

The US faces complex challenges in its Middle East policy amid the Israel-Hamas conflict. The US’s inability to broker a ceasefire in Gaza not only exacerbates regional instability but also diminishes its credibility as an effective mediator. Additionally, the US’s unwavering military support for Israel, although in line with its longstanding policy of ensuring Israel’s security, has sparked concerns among allies like Egypt and Jordan, both of whom fear a potential influx of refugees from Gaza and the West Bank. These dynamics weigh on US efforts to normalise relations between Israel and Arab countries, especially Saudi Arabia, where public sentiment strongly favours the Palestinian cause. Moreover, US military actions against Iran-backed militias in Iraq have worsened US-Iraq relations, complicating the US’s broader regional strategy.

Domestically, President Joe Biden’s firm support for Israel has alienated many Arab and Muslim American communities, who have refused to support him in the upcoming 2024 presidential elections. This intricate landscape of internal politics and external policy challenges presents the US with a daunting task of harmoniously aligning its strategic objectives, moral responsibilities, and the varied expectations of both domestic and international actors, to navigate a multifaceted foreign policy landscape.

Lines in the sand

Despite significant hostilities in recent months, the US and Iran have also shown some restraint, indicating their shared reluctance for wider conflict. This cautious approach is reflected in the US only responding to attacks by Iran-backed militias – and striking the Houthis with the stated objective of protecting international shipping – but avoiding strikes on Iran or Hezbollah. Similarly, there are signs that Iran has been trying to rein in its proxy militias in Iraq and Syria. However, some actors, such as Israel, Hezbollah and the Houthis maintain considerable autonomy, and have demonstrated limited appetite for major compromise. In their efforts to achieve deterrence against their rivals, a single miscalculation can lead to an irreversible escalation, resulting in a conflict in the Middle East of a scale and complexity not seen in recent decades.