Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) in Africa is made up of complex networks and relationships, traversing both regulated and illegal activity. Despite being a source of income for local communities and migrant labour, the very nature of ASGM makes it intrinsically vulnerable to exploitation. This is exacerbated by the fact that ASGM activities often take place in remote locations, and in the shadow of larger commercial operations.

Some governments have sought to regulate this largely informal sector, recognising the need to protect and support artisanal miners. Yet, political will is typically diluted at the grassroot levels, with local authorities unable or unwilling to implement regulations. Many local officials are themselves complicit in associated illegal activity, allowing organised crime syndicates to subvert or co-opt many ASGM operations across the continent.

Therefore, although illegal ASGM has previously existed in parallel to the formal sector, spill-over violence and, more recently, the infiltration of militants in ASGM areas, have given rise to new for nearby industrial sites.

The Mining / Militancy Nexus in West Africa

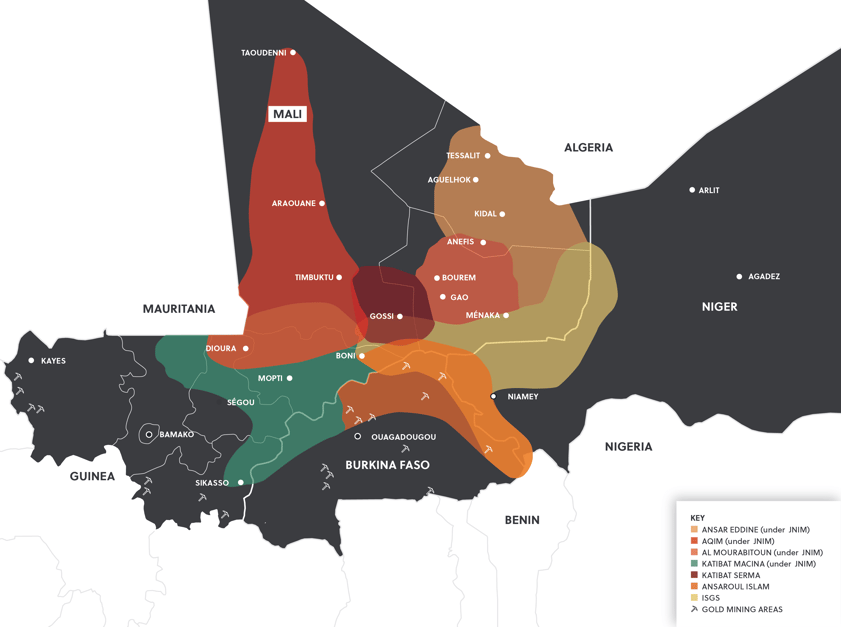

While historically the evidence tying precious metals to terrorist networks has been anecdotal, government officials in West Africa have consistently flagged the potential for high value commodities like gold and diamonds to serve as alternative currencies in money-laundering schemes and terror-financing. Now, there are growing signs that Islamist militant groups are more directly involved in ASGM operations.

In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, new ASGM sites have sprouted in militant-controlled territories, such as Mali’s Kidal and Tessalit areas and Burkina Faso’s Soum province. Furthermore, advancing Islamist terror groups such as Jamaat Nusrat Al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) have expanded into traditional artisanal mining territories. Already, in Burkina Faso, grassroots Islamist group Ansaroul Islam has attacked several ASGM sites in Soum Province, reportedly seizing several operations where militants continue to extort local miners.

The transient roles of artisanal miners, traffickers and militants - themselves typically members of surrounding communities - adds further complexity to this nexus.

The transient roles of artisanal miners, traffickers and militants adds complexity to the mining/militancy nexus."

Markedly, the overlapping territory of ASGM and industrial sites places militant groups physically closer to commercial operators, the consequences of which are already evident. Ansaroul Islam alone has been linked to several attacks against mining operations in Burkina Faso since October 2018. On 4 October 2019, for example, the group attacked a gold mining site at Dolmane, Soum Province, killing at least 20 people. Ansaroul Islam is also believed to be responsible for the 6 November 2019 attack against the vehicle convoy of the SEMAFO mining company in Burkina Faso’s , in which 37 people were killed; the mine only reopened in September 2020. Prior to this, in 2017, the group was behind improvised explosive device (IED) attacks targeting convoys serving the Inata mine, Soum Province. These attacks, coupled with financial and technical factors, resulted in the temporary suspension of operations at the Inata mine.

Across the border in Niger, authorities have flagged the proliferation of gold prospecting sites in the northern Djado and Aïr regions, which continue to be largely ungoverned spaces where narcotic and other illicit trafficking are pervasive.[1]

Islamist militant groups have entrenched their operations in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso’s rural areas. Although Western and regional governments remain committed to counter-insurgency efforts across the Sahel, Islamist militant groups have proven highly adaptive to these operations. This is, in part, due to their ability to leverage local networks, which now include part of the ASGM sector. Mine operators in the region should pay close attention to the militants’ expanding reach, which is now bolstered by possible gold revenues.

Islamist militant groups have proven highly adaptive to counter-insurgency efforts.”

Zama Zamas and the Criminal Underworld of South Africa

South Africa’s ‘Zama Zamas’ – the local term used to describe illegal miners, cost the economy USD 1 billion in lost production annually, making the country among the largest exporters of illegally-sourced gold in Africa.[2] This sum does not include the concealed impact and costs of increasingly violent criminal dealings in the illegal ASGM sector, which include damage to private and public infrastructure and, in severe cases, loss of life.

Illegal ASMG syndicates typically operate in South Africa’s disused mines, meaning that, unlike gold panning operations elsewhere on the continent, artisanal mining in South Africa compromises large networks of underground cities where extortion, forced labour and violent turf wars are commonplace. Above-ground mass executions have also been reported in the previous mining hub of the East Rand, Gauteng Province, on several occasions.

Artisanal mining in South Africa compromises large networks of underground cities where extortion, forced labour and violent turf wars are commonplace.”

The Department of Mineral Resources estimates that there are 6,000 such illegal mines in South-Africa, many located in the wealthiest Gauteng Province, and that 70 percent of Zama Zamas are undocumented migrant workers.

The system exists within the context of South Africa's worsening crime crisis, supported by organised human, weapons and precious metals trafficking. According to the global think tank Institute for Economics and Peace, the costs of violent crime in South Africa amounts to 13 percent of GDP.[3] On average, violent crime costs countries 8.8 % of GDP globally. Pervasive crime and ineffective and, at times, complicit police services mean that the burgeoning crisis in South Africa’s ASGM sector has largely gone unchecked.

Growing underground operations, as well as competition among Zama Zama syndicates, have meant that these groups are infiltrating industrial mining sites more frequently. Many commercial operators are now increasing spending on upgraded security infrastructure and other protocols to combat Zama Zama activity within their boundaries and its consequences, such as damage to equipment and the collapse of mine shafts.

The implications of poor practices in illegal mining are wide reaching, with the City of Johannesburg citing irresponsible and illegal blasting as a key cause for tremors which could impact the physical integrity of surrounding infrastructure. While the government has created a dedicated task force to address issues of illegal mining, very little progress has been made. This comes in the absence of clear policy and legislation, with the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), for example, under review since 2013.

Criminal mining hierarchy in South Africa:

Treating the symptom

While several governments, including Mali and Ghana, among others, are seeking to formalise the ASGM sector[4], greater regulation alone is unlikely to combat the growing security ramifications of the practice. The unbundling of the artisanal mining, trafficking, crime and militancy consortia cannot be separated from wider socio-economic and governance challenges which drive insecurity in parts of the continent.

In the absence of a comprehensive and effective solution, commercial operators will have their own part to play in navigating the ASGM / crime / militancy risk landscape. Monitoring the evolving threats and preparing appropriately is paramount to staying ahead of the associated risks to business in these dynamic operating environments.

Commercial operators will have their own part to play in navigating the ASGM / crime / militancy risk landscape.”

References

[1] OECD & The Liptako–Gourma Authority. (2018). Gold at the crossroads: Assessment of the supply chains of gold produced in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

[2] Martin, A. (2019). Uncovered: The dark world of the Zama Zamas. Enact Africa.

[3] Institute for Economics & Peace. (2015). The Economic Cost of Violence Containment.

[4] MacQuilken, J., & Hilson, G. (2016). Artisanal smal-scale gold mining in Ghana. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.